This article has been written and published for Real Archaeology, an online event where a number of creators are producing archaeology-related content on various platforms. Like with any game inspired by Dungeons and Dragons, one… More

Why the dark academia aesthetic for the archaeologist doesn’t (but could) work

I’m not one for internet aesthetics. Before I studied archaeology, I was very much into the mainstream. I spent most of my time not reading the great classics, Fitzgerald, Carver, Dickens, but Sophie Kinsella, Helen Fielding and oh god R.R Martin. I rolled my eyes when anyone mentioned Plath or Hughes, there was very little time for anything much else but attending ritzy media parties. When I was at university for my postgrad, archaeologists fell in two camps, the pseudo academic always with a book in his hand or the scruffy muddy handed digger. Unfortunately for me I probably fell in the former category, although I found my tweed collection was lacking in comparison to everyone else and my knowledge of Latin was subpar, but who knew that almost a half a decade later that this image of the pretentious scholar would somehow end up being an internet sensation? Dark academia as it is known as is a popular academic aesthetic on social media that revolves around classic literature, the pursuit of self-discovery, and a general passion for knowledge and learning.

At 33, I am beyond the pursuit of an idolised image, but what intrigued me about this weird corner of the internet was how much of archaeology, most importantly an era of archaeology known as cultural history revolved around this aesthetic. Did the understanding of the origin of archaeology play almost ironically in this aesthetic? For those who don’t know, cultural history was based on the idea of defining historical societies into distinct ethnic and cultural groupings according to their material culture. It was first developed in in Germany among those archaeologists surrounding Rudolf Virchow, culture-historical ideas would later be popularised by Gustaf Kossinna. A staunch nationalist and racist, Kossinna lambasted fellow German archaeologists for taking an interest in non-German societies, such as those of Egypt and the Classical World, and used his publications to support his views on German nationalism. This makes the idolisation of scholars from this period, problematic. There are numerous articles on this subject, most criticising the European aesthetic of the academic. And much like cultural history, it is defined by elitism with undertones of racism and classism.

Bruce Trigger argued that the development of cultural history in part was due to the rising tide of nationalism and racism in Europe, which emphasised ethnicity as the main factor shaping history. Childe introduced the concept of an archaeological culture (which up until then had been largely restrained purely to German academics), to his British counterparts. This concept would revolutionise the way in which archaeologists understood the past, and would come to be widely accepted in future decades. The pictures that encompass this aesthetic mostly focus on the European ideals. There is nothing intricately wrong with wearing tweed and reading Homer’s Iliad, but there seems to be little awareness of were this aesthetic borrows heavily from the colonial period of British history. Dark Academia glorifies the long relationship between colonialism and archaeology. Even if one is not studying archaeology, the aesthetic (predominantly the fashion and décor) borrow almost exclusively from culture historians. From tweed jackets to pith hats, certain items of clothing are enduring emblems of preconceived notion of “European intellectual supremacy”.

A famous archaeologist Dr Manassa Darnell also known as the “Vintage Archaeologist” has a large Instagram following, and presents herself as a 1920s Egyptologist of course from a white European or American with a particular socio-economic background. During this period, archaeological practices not only sidelined African people’s heritage and knowledge. They also resulted in many important fossils and artefacts being held in institutions outside Africa most notably America and England. The obsession with the aesthetics of a particular culture and era are questionable, there is of course nothing wrong with appreciating beauty and aesthetic on any level. The issue arises when people who follow this aesthetic celebrate colonial-era archaeology and erase the presence of people of colour. Dark Academia promotes the marketization, and consumption of these type of colonial aesthetics.

With a focus on the idolisation of classical art and philosophy arguably beginning at the same time as cultural history or at least in colonial era archaeology. The Elgin Marbles of the Parthenon for example were removed between 1801 to 1812 by agents of Thomas Bruce, 7th Earl of Elgin, as well as sculptures from the Propylaea and Erechtheum. The resurgence of Greek and Roman imagery by extreme conservative, white supremacist groups show how these types of imagery are still powerful at degrading people of a non-white background. Presumably, the problem is then not the aesthetic itself, I own a patchy armed tweed jacket, and my khaki’s are what I pack during archaeological excavations, it lies is in the complete idolisation and ongoing popularity of and nostalgia for colonial imageries among large segments of western audiences. By replicating this period down to the Harris Tweed and ignoring the the Eurocentrism apparent in Dark Academia makes it problematic in the context of the contemporary archaeology. In this light, it almost callous for scholars of this field to out rightly appeal to the white-washed, elitist nostalgia of cultural history without context. It is up to us to instead point out the irony of internalised coloniality, and wear those tweed jackets while rewriting the damage done by those before us.

Space Archaeologist: Liara T’Soni

Guest Post by Franki Webb, an archaeologist and writer. She started as a journalist but decided to chase her dreams of being an archaeologist. Her writing mostly focuses the problematic nature of Western archaeology and archaeology in the media. Currently she is working as an archaeological consultant for an engineering company.

Sarah Parcak, author ofSpace Archaeologydefines the discipline as “any form of air or space-based data to look for ancient features or sites.” Space Archaeology is very much a real discipline, steeped in using the latest satellite data to find new archaeological sites normally difficult to see on the ground. This is very different to how archaeology is usually depicted in a number of videogames, such asUncharted(2008) andTomb Raider(2013), where data is curiously absent. Undoubtedly, audiences are familiar with archaeological themes in science fiction movies such asForbidden Planet(1956);Planet of the Apes

View original post 753 more words

We are not Imposters: Dealing with Impostor Syndrome and archaeology

I don’t think I’m the only female archaeologist who’s looked around a room and thought what the hell am I doing here? I regularly do this, and I’m training my brain not to allow these thoughts to take over like Dory from Finding Nemo I constantly repeat “Just keeping nodding, nodding”. Because these thoughts are insidious, they creep up on you in the middle of a sentence, as you enter a conference room, or even when writing an email. The feeling is everywhere. I once was invited to speak at a conference on the topic of archaeogaming. My online articles had proven popular with a number of people following the subdiscipline and I felt absolutely ecstatic to be recognised. The conference moved online and even from the comfort of my own sofa, I felt like I wasn’t supposed to be there. Apparently a lot of archaeologists feel the same, a quick search of the terms “imposter syndrome” and “archaeology” on Google, produces 1,030,000 results. A lot of archaeobloggers like myself have posted about it, feeling the weight of their own inadequacy, most of which are women and underrepresented racial, ethnic, and religious minorities, hardly surprising when you look into the evolution of the subject.

Like most of them, I can almost pinpoint where my imposter syndrome took hold. This feeling started off during my postgraduate studies, I sat in my Archaeological Theory class in University College London, tired and exhausted from trying to understand the amount of assigned readings from the night previous. Words like “processualism” and “middle range theory” popped out of my head as quickly as they got into it. Impostor syndrome is not the root cause of the problem, I realised that after taking Cognitive Behavioural Therapy that my worst enemy was not the lecturer probing me for comebacks on my theory, or that overenthusiastic undergrad asking me the impossible questions that I needed a reference for. It was me. I was the one with these thoughts in my head after all.

When I was talking to my therapist, she noted that I constantly put myself down. “Sorry I’m just being stupid” was/is apparently one of my favourite phrases or my ultimate favourite was/is “I’m a bit of an idiot.” According to Marisa Peer, author of I am Enough repeating negative phrases about oneself makes the mind believe them. So the fact I was talking to myself in such a negative way almost everyday made me believe I was in fact “stupid” and an “idiot.” When I decided to do a presentation for the local history group about the archaeology of our area I walked in thinking “I’m too stupid to do this”. During my undergraduate studies I did a presentation comparing the use of Jade in Neolithic China to to that of the Classic Maya in Mexico. I remembered being so filled with confidence because I kept saying to myself “I can do this” something one of my favorite videogame characters Lara Croft repeatedly says to herself during the course of the game Tomb Raider. The power of my own words had changed my outlook so quickly. So what changed? Having strong role models is imperative to development when I had just started off I latched on to strong independent thinkers who not only encouraged me but who took their own time to help me. When they moved on I felt isolated and alone, and worried about my own capabilities.

As archaeologists we aren’t supposed to know all the answers. Within my career, I have known academics who know very little about digging, and I have known fieldwork archaeologists who struggle to present their ideas to an audience. What’s important even if you know you have weaknesses you can change them with some discipline and self belief. It’s really that simple. During this last week, I realised one of the most important things for me is writing, be that on this blog, journal or website. I took Peer’s advice and started writing a little everyday so it would become a habit. When you repeat the same action every day, even if it’s only for ten minutes you start adopting healthier habits. I started by writing ten minutes of my blog, and started writing a new article, by the end of the week I had three ready to publish articles! One of the persistent worries I hear from other archaeologists is that they don’t know enough especially from students, when I was helping them study Aztec hieroglyphs I told them to learn just one every day. Once they have memorised one, they could easily memorise two.

Let’s be real even if we don’t want to admit it, but Imposter Syndrome is ubiquitous with archaeology because of the very nature of the subject. The material culture reveals a number of traits regarding human behaviour, but human behaviour by it’s very nature is capricious especially during periods when humans weren’t fighting for survival. This means archaeologists can never really assert a clear and standard theory to explain human behaviour, which can make us feel somewhat unqualified. But none of us can really be fully qualified to make such assertions without a time machine. We can make informed theories even if we can’t prove them. The archaeologists that I have great respect for know this. They’ve also trained their brains to accept this and not strive for absolutes. These feelings are the hijackers sabotaging our rational brain to make us believe the feelings instead of the facts. As archaeologist even if we accept that our ignorance of their world is vast, we can’t allow impostor thoughts to block our pursuit of knowledge.

An Archaeologist Reviews – The Dig (2021)

The Dig is a film driven not only by discovery but by loss. This feeling is captured in everything from it’s melancholic characters to its muted but earthy cinematography. The movies tells the story of Edith Pretty (Carey Mulligan) who hires local self-taught archaeologist-excavator Basil Brown (Ralph Fiennes) to tackle the large burial mounds at her rural estate in Sutton Hoo near Woodbridge. He and his team discover a ship of Anglo Saxon origin while digging up a burial ground. It’s an archaeological discovery that lit up the Dark Ages. Before this discovery, a dearth of written sources was presumed to signal an absence of culture in this period.

The greatness of The Dig lies in its look at the personal lives of the people behind The Dig even if entirely fictional. This Netflix production focuses on how the key themes of archaeology such a death, loss and memory affect the characters. Brown struggles to maintain his control over the site, with Pretty, who’s going through health issues, not always available to make sure the right thing is done. But both share a passion for knowledge, for discoveries of the linkages between eras and peoples.

Based on John Preston’s novel of the same name, The Dig is a story laid out in truth, allowing the historical events and somewhat realistic characters to keep the viewers captivated rather than need for excessive drama caused by snakes, guns, treacherous Nazis or damsels in distress. The most important aspect is not the treasure found, but how the knowledge has impacted our lives. Allowing us to reflect on our complex relationship to the past, and how and why we value it. For a nation on the brink of war, the discovery of Sutton Hoo was a source of pride and inspiration, equivalent to the tomb of Tutankhamum.

The funerary mound contained the remains of a decayed oak ship, approximately 27m in length, which had been dragged from the nearby River Deben to serve as a royal tomb. Over 250 artefacts revealed the sophistication of East Anglia in Anglo-Saxon times. There were riches from across the known world, including silver bowls and spoons from Byzantium and gold dress accessories set with Sri Lankan garnets, highlighting that trade was happening on a large scale even then. The wood of the ship and the flesh of the man had dissolved in the acidic Suffolk soil, the gold, silver and iron of his wealth remained. The burial is thought to belong to King Raedwald, whose reign corresponded with the early seventh-century date of the coins contained in a gold purse (c. 610-635CE).

The movie gives us an portrayal of the archaeological excavation in the 1930s, conducted using workmen with just a few skilled excavators and qualified academics. There is careful attention to archaeological detail, emphasising that the ship’s timbers had virtually disappeared, surviving as nothing more than iron rivets and a silhouette stained in the sand. But with all its triumphs, The Dig fails to cast it only female archaeologist in a positive light, Peggy was known during her impressive career for her field expertise, but she is relegated to love interest for a swoony Johnny Flynn, her brilliance rarely shown. But that’s true for the rest of the dig team, few professional skills are depicted at all: the archaeologists were brought in to draw, plan and record archaeological features – not simply to extract artefacts.

The final scenes reburying the ship to protect it during the impending WWII shows that Britain is to bear even more loss within its history. Director Simon Stone explores the idea of having a legacy, the emphasis in the movie is what we leave behind for others. Thankfully for us, Brown and Pretty’s legacy is on permanent display. The finds were given to the British Museum to ensure that they were accessed to as many people for free allowing the treasures to be found again by new generations. Deepening our understanding of ourselves, our world, and our collective history.

Detoxing from cultural heritage

Like nearly everyone else in the UK I have spent most of the last year either indoors or in a park. Gone are the days when I would take detours through the British Museum to get to my part time job. There hasn’t been a day when I haven’t thought about the exhibitions that have been cancelled, or the empty spaces within those walls that I used to escape to when the stress of everyday life got too much.

The hiatus of not visiting my favourite cultural spaces has allowed me to rethink about why I spent so little time focusing on my needs away from work and study. My life has revolved around archaeology for such a long time that I had forgotten about the other parts of me that made me well me. How many exhibitions can I attend? How many books can I read this week? It was mentally exhausting, and while I still have guilt pangs about how much I’ve missed, the truth is so has everyone.

The freedom not to focus too much on keeping up to date with the latest research and exhibitions has allowed me to focus on myself, reading for the love of it, writing because I want to and not because of a false pressure to get published. Prepandemic I was only focused on how aspects of cultural heritage could either improve my knowledge or how it could impact my work. There’s much more to cultural heritage than what people are finding or how it looks in pretty display boxes. It’s about how we connect with it. Do we see our ancestors faces when we read about their ideologies? Do we see current patterns emerging when we walk around the ruins of fallen civilisations? This is what makes cultural heritage relevant to the world.

Detoxing from it, has allowed me to take a step back and consider what I enjoyed about it initially. The truth is people perspectives on it has always grabbed my imagination. How video game designers create spaces in historical environments. How people look at monuments and decide what people were thinking within that time and landscape. How writers use historical events and places to create narratives that connect with audiences.

The pandemic has allowed lots of us to look more inwards and to think about our happiness and contentment. The lives we were living before might not have actually been the best for our mental health, we’ve (or most) had the opportunity to slow down and reevaluate our goals, this inevitably means we’ve discovered something new about ourselves or that we don’t actually know ourselves at all. Cultural heritage won’t be the competition I wanted it to be. I will read books, attend exhibitions, and watch documentaries but in healthy moderation.

Video games inspire us

“All men dream – but not equally. Those who dream by night, in the dusty recesses of their minds, wake in the day to find that it was vanity… But the dreamers of the day are dangerous men, for they may act their dream with open eyes, to make it possible. This I did.” From T. E. Lawrence’s Seven Pillars of Wisdom.

I get asked a lot, “how did you get into archaeology?” it’s not a question I like to answer. I find myself tugging on the ends of my sleeves, an awkward reflex I picked up during the tortuous years of high school. The truth is I always lie when I respond to this question. I lie quite unabashedly about getting interested in archaeology in my teens, but the truth is archaeology never really crossed my mind until my early twenties. I’d always loved history; castles and I took delight in Indiana Jones as a kid but that was the extent of my appreciation for the discipline. The reality is videogames got me interested in archaeology, and not just any video game, Dragon Age. I loved the series so much, but it wasn’t just the storyline or characters that sucked me into the world, it was the world itself: scattered ruins, ancient races, forgotten languages and mystery hidden behind every corner.

The environs of Dragon Age got me thinking of historic landscapes in my country, England. I started visiting ruins of abbeys some which could be picked straight out of Ferelden. I loved the symbolism found in Celtic crosses and was drawn to the preserved landscapes of the prehistoric. After a year of making the most of my English Heritage membership I knew that I wanted to pursue something that made me fulfilled, much like how video games had made me feel. I applied for a degree that year, and continued playing video games with archaeology as a focal point, Tomb Raider and Uncharted. My archaeology origin story was one I didn’t like to share with others at university who usually had the typical story of joining their father’s excavation at Durham or found their first piece of worked flint at the age of 8.

Video games have always influenced my life and for the most parts in truly positive ways. It was my love for video games that led me to Japan when I was 20, got me into sewing as I recreated outfits of my favourite characters. It’s how I met my best friend, my first boyfriend, it’s provided me with a number of positive female role models throughout my adolescence and early twenties. It provided escapism when life just got too tough, allowing me to switch off the static around me. The role video games has had on my life and career has been unmeasurable, I owe Square Enix, Bioware and Core Design my sanity and happiness. When parents complain about their kids on that damn Xbox all the time, don’t automatically think they are wasting their time. It’s likely they are being inspired for the rest of their lives, to take risks they probably wouldn’t take outside of the safety from their own living room. To think outside the box, to study astrophysics to be like Commander Shepherd, to be fearless like Ellie or to create their own video games as a writer, artist or composer. That’s because video games inspire us.

Queen Himiko of Japan – The Archaeology Behind Tomb Raider (2013 & 2018)

“Myths are usually based on some version of the truth”

– Lara Croft, Tomb Raider

There was something to admire about Crystal Dynamics’s 2013 video game Tomb Raider, Lara Croft, the main protagonist’s of the franchise is a keen archaeologist and like many wide-eyed archaeology graduates wants to make a name for herself. In this rendition, her interest in exploration focuses much more on the archaeology she hopes to discover than the treasure she uncovers during her time as PlayStation’s pinup girl of the 90s. In the 2013 game, recent archaeology graduate Lara Croft travels to a lost island off the coast of Japan in search of the lost kingdom Yamatai. Unfortunately for Lara and her comrades, the island is crawling with cultists known as the Solarii, and soon she forced into a battle of survival as she tries to escape the cult and the a supernatural presence that is chasing her.

Like many gamers, I loved this version of Lara (before the daddy issues came along, damn you Rise), and as an archaeologist interested in East Asian prehistory, this setting sparked intellectual joy (thanks Marie Kondo) unlike the previous games, which stuck to the fail safe of pyramids and King Arthur. There aren’t many faults with this game, and like Lara I too became captivated by the legendary figure of the Sun Queen, Himiko.

In the game Queen Himiko (卑弥呼) serves as the antagonist to Lara Croft, creating a supernatural entity Lara not only has to fight but also has to use her wits and intelligence to keep one step ahead. A formidable opponent for Lara, the spirit of the ancient Sun Queen is transferred from body to body through ritual female sacrifice. Himiko is essentially a plot device that allows Lara to realise her full potential as an archaeologist and tomb raider as she tries to solve the mystery of the island and its inhabitants.

A quick history

Queen Himiko was the shamaness ruler of the Yamatai kingdom, an area of Japan considered to be part of the country in Wa (Japan) during the late Yayoi period. Himiko is not mentioned the first history books Nihon Shoki (720 AD) and Kojiki (712 AD). She is however mentioned in Chinese history books, specifically the he c. 297 Records of the Three Kingdoms (Sanguo Zhi 三國志). These Chinese sources portrayed Himiko as a mighty sorceress and there are several such characters in Japanese history who could fulfill that role. Scholars in the 17th century proposed Empress Jingu. She became the defacto ruler of Japan in 201 AD ruling for the next 68 years until her death at the age of 100. However, Chinese sources claim when Himiko died there was a prolonged period of civil war which ended in the Yamatai making another woman their Shaman-Queen, a woman called Iyo (壹與). Jingu was succeeded by her (possibly illegitimate) son, Ojin.

However, the biggest mystery that still lingers till this day is where was the kingdom of Yamatai? In the video game Yamatai is depicted as having multi-period occupation island, but archaeologists believe the real Yamatai to have existed in some form in Kinki, the Yamato region of Japan.

The Yamatai Controversy

Known in academia as “The Yamatai Controversy” , in the last century archaeologists and historians had two main contenders for the location of Yamatai. Kinki in the Yamato region of Japan and Northern Kyushu. However, an account by a Korean itinerary to Yamatai in Wei-shu disputes the theory that the kingdom was that far south in Kyushu.

It is likely that the kingdom was close to the old capital of Nara within mainland Japan, a potential archaeological site has been linked to Yamatai in Hashihaka. In 2009, excavations in Makimuku ancient ruins in Sakurai revealed the Hashihaka tomb, dating back to the late third century, and is said to be the location of the tomb of Himiko. The Makimuku ruins measure about 1.24 miles (2 kilometers) east to west and about 0.93 of a mile (1.5 km) from north to south. The ruins have ancient burial mounds, and a 306-yard (280-meter). In 2015, further investigations showed a burnt boar scapula found in the ruins of Makimuku, which may relate to the practice of burning animal bones to tell the future. The boar bone found at Makimuku measures 6.6 inches (16.7 cm) long by 2.64 inches (6.7 cm) wide. A further 117 frog bones have also been found at the site and there is a suggestion that they may have been used as an offering to the gods or in some other kind of religious rites.

Shaman Queen

In the video game Tomb Raider, Queen Himiko is said to have shamanistic powers and abilities, and there is some truth to this. Himiko is said to have practiced guidao, or Japanese kido, a type of Daoist folk religion. The Gishi no Wajinden (魏志倭人伝, ‘Records of Wei: An Account of the Wa’) described her as a having “occupied herself with magic and sorcery, bewitching the people”. She was seldom seen in public and was attended by “one thousand attendants, but only one man”. Like the video game, Himiko had many female attendants and a legion of skilled warriors who were sworn to serve and protect her known collectively as the Stormguard. They guarded her decaying body until Lara is forced to fight them to get to her tomb to save her best friend Sam from being another sacrifice.

The archaeological record shows reveals that some of these myths might have some basis in the truth. Between 1955 and 1964, a series of archaeological discoveries including the excavation of a tomb near Kyoto with numerous bronze mirrors possibly dating from the 3rd century. A mirror, known as Himiko’s mirror, was found in the Higashinomiya Tomb in Aichi, Japan. Researchers analyzed the “mirror” and found it had a slight unevenness to its surface – so slight the naked eye cannot recognize it. The uneven surface creates patterns on the back as light reflects off of the front of the mirror, seeming to project a magical image.

Tomb Raider 2018

Unlike the 2013 game, Tomb Raider the movie released in 2018 starring Alicia Vikander as Lara, takes Himiko in a completely different direction depicting the queen as the “Mother of Death”. The movie has a big twist, unlike the game Himiko isn’t mystical, (the real Queen Himiko probably couldn’t control storms or transfer her essence across bodies) but rather she was the carrier of a deadly disease. Furthermore, she wasn’t malicious; in fact, she exiled herself to Yamatai to prevent the spread of the sickness. There is no mention of her shamanic abilities or her role as a religious figure, which spurs the video game’s main antagonist Mathias, who’s been stranded on the island for 31 years, to worship her. Yet, like her real life counterpart she is still shrouded in mystery and intrigue.

The real Himiko’s legacy is a reminder of how historical women figures are often forgotten. She doesn’t feature prominently in the history of Japan, and recognition as a ruler didn’t come till the Edo period in the 1600s. It is likely that the Japanese adoption of Buddhism and Confucianism didn’t do much to elevate the status of women. Fortunately, she wasn’t permanently erased. Himiko represents the first notable ancestor of a strong tradition of female religious leaders and political leaders in Japan and serves as a representation of the unnamed women forgotten to history.

An Archaeologist Recommends, Quarantine Books – Must reads! Part 1

Like so many self-isolating, quarantining, social-distancing or whatever you want to call it from COVID-19. I have found myself comforted by the array of books on my dusty shelves. I’ve picked up books that I bought months ago and later discarded, I’ve re-read books that I definitely forgot about and like many others have purchased books that I’ve always wanted to read, but just never had the time.

So I’m pleased to outline some of my faves, these three books focus on archaeology/history. Have any books you can recommend a bored, creatively-starved archaeologist? Please comment.

1. Breaking the Maya Code by Michael Coe: The book tells the story of how a group of archaeologists with different expertise manage together to crack the Mayan hieroglyphs. It’s told in stylish prose not often seen in many academic books, and this is why it’ one of my favourite books. It’s THE book that got me serious about archaeology. It’s an easy read, and takes the reader into the thought-process of interpretation that many archaeologists shy away from explaining.

2. Sapiens by Yuval Noah Harari: While strictly not an archaeology book, Sapiens tells the story of the human race from its first origins in Africa all the way to the present day. Personally as an archaeologist who’s interested in the bigger picture, books like these always peak my interest. The author doesn’t shy away from explaining complex issues in a way which can actually be understood and comprehended by most people. The book is based on the author’s own opinions and thoughts about the human condition and character, which is welcoming change from most books dealing with the human history.

3. The Parthenon by Mary Beard: Beard can definitely be hit or miss. But the Parthenon is definitely a hit. The books gets into the details about one of the most famous buildings in the world. The book takes us back in time describing how the temple was constructed and uses throughout history. It’s the ultimate tour of the past and present state of this glory Acropolis.

An Archaeologist Reviews Detectorists

The are so many movies and TV shows that use archaeology as their main premise, and much of the time they fail to capture its pure essence, instead focusing on the mythical, the adventure, the extraordinary. But a lot of the time archaeology can be really mundane. The excitement an archaeologist can experience finding a coin is rarely portrayed in film and I understand why: why would an audience want to watch the mundanity of anything, but that’s exactly what makes BBC’s Detectorists so inspiring. It is about the ordinary, the unexceptional and the insignificance of every day life.

Middle-aged detectorist friends Andy (Mackenzie Crook) and Lance (Toby Jones) blissfully while away their afternoons sweeping electronic wands across the local fields in an perpetual search for ancient treasures. Their time in the field offers them a brief reprise from the humdrum of everyday life. Written and directed by Crook, the BAFTA winning show starts with the two leading characters in not such a good place. Andy is unemployed and Lance is bullied by his ex-wife who left him for another man.

The concept for the Detectorists is novel, character driven focusing on the emotional truths of being misfits. Throughout their time as members of the Danebury Metal Detecting Club, they’re transformed into time travelers and explorers, experts in their specialized field. In the first season, Andy and Lance are convinced that their favourite territory contains a Saxon treasure trove, but they usually go home empty-handed, probably to the joy of many archaeologists watching.

In reality, many archaeologists dismiss detectorists as mere treasure hunters. There’s truth in this, in the last decade metal detectorists increasingly impinge on archaeological sites, leaving damage and removing artefacts, many of which are finding their way to antiquities dealers or even leaving the country. But Crook wants the audience to know his characters aren’t like this, deliberately adding a line where Andy says “I don’t sell my finds, I don’t agree with it. When I am a qualified archaeologist that’s when I get to see the good stuff.”

And it’s true detectorists spend their weekends braving driving wind and rain, and have been responsible for a series of spectacular finds in recent years. Not all are criminal detectorists stealing artefacts in the dead of the night. Anyone who’s encountered one in the field knows that those strange whistles and beeps of a metal detector can conjure up a special kind of magic. An excitement even in the most seasoned archaeologist can’t resist.

And the flip-side of the treasure-stealing detectorist is the dismissive commercial archaeologist. Andy, who qualified as an archaeologist in a the second series, finds himself working on a commercial dig. The site manager suggests getting rid of the Roman mosaic floor, which Andy has recently discovered. The underlying message is that commercial archaeology sometimes fails to identify and protect archaeology that may get in the way of their client’s development. Crook seems to be suggesting that by becoming so close to developers archaeology has lost its innocence, it’s true meaning.

The Detectorists explores the state of our archaeology and our attitudes to the past from the keen hobbyist to the overworked professional. Sir Mortimer Wheeler famously said “In a simple direct sense, archaeology is a science that must be lived, must be “seasoned with humanity.” Dead archaeology is the driest dust that blows.” And that’s what this BBC shows does, it tells the story of a bunch of enthusiastic hobbyists quietly living for the next time they unearth more of our history.

The Archaeologist’s Ikigai (生き甲斐)

Like many within the current isolation bubble (COVID-19 for time-travellers reading this) I have turned to more soul-searching ways to burn daylight. I often find myself browsing through the various books on my wishlist on Amazon, looking for something that might answer the nonsensical questions buzzing around my weary mind.

I finally managed to get around Tim Tamashiro’s book on How to Ikigai. There are many ways in which I strive for a fulfilling life but like most I have found myself stuck in a rut, feeling the opposite – unfulfilled bogged down by societal expectations and entrenched daily routines.

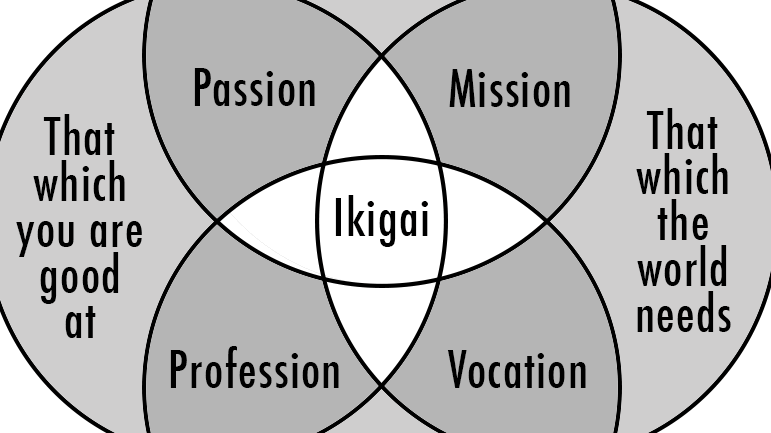

Ikigai (生き甲斐, pronounced [ikiɡai]) is a Japanese concept that means “a reason for being”.

A reason for being is not as simple as it seems, because like most things our Ikigai is intertwined with modern day society expectations – paying the rent, having a family and public perceptions on what it means to be “successful”. That’s the problem for millions of people: how can you feel fulfilled when you’re constantly weighed down by burdens such as financial responsibilities and built -in routines – all of which dominate our lives?

Well let’s break it down: there are four parts to Ikigai, which roughly translates to:

- What do you love?

- What are you good at?

- What does the World need?

- What do you get paid for?

For myself the answer for the first question comes quite easily: archaeology. But does doing what you love translate well into doing what you’re good at? This is where for a long time I dawdled on the concept of Ikigai. What does being good at archaeology truly mean? Does it mean I understand the patterns of human behaviors? Good knowledge of human history? Or am I really exceptional at digging holes?

Before I decided to become an archaeologist, I developed a talent for understanding the detail, which made my articles about Japan and history insanely popular when I freelanced as a journalist. My sense of belief and purpose however still remained on an individual level, despite spending a lot of my young adult life in a country (Japan) that focused on the collective rather than the individual. But most importantly my talents didn’t necessarily connect with my passion.

After years of studying and traversing the perils of academia I soon realised that scholarly archaeology was nothing more than fanciful projects appealing for funding and getting lost in the bibliography of quite dull publications. For many of us archaeology is still entrenched in layers of jargon and dryness. While museums and television programmes allowed for the public to view archaeology from an outsider’s perspective the feeling of inadequacy still permeates people’s understanding – the leave it to the experts sentiment is felt throughout “amateur” spheres and casual participants. Is archaeology delegated to academic research in ill-forgotten journals? Yes, but it is also so much more, it’s about understanding our ancestors’ story. A story which in theory should be available to everyone.

The story is out there within the dusty books lying on library shelves, the unpublished papers saved on hard drives, and the bones left in boxes stored in forgotten archives. Our Ikigai is clear: the world needs for people to feel connected with their past. We need people to connect to their past just as much as they connect with their present and future. For the longest time in my life I was paid to write, to make the mundane interesting and informative, when I gave it up to pursue my passion for the human past I thought no more of connecting with audiences through the medium of word.

But the medium of word is flexible, it’s multifaceted, while many academics frown upon the flowery and indulgent prose littered in popular non-fiction it’s a tool, a weapon against the tedious monotone of academic writing. People might walk around the ruins of a fallen civilization taking in the awe and other-worldliness, but that’s no use if the visitors don’t understand it’s significance.

If archaeologists really care about the past and what it means then their ikigai needs to be conveying the story to the masses in every medium possible through art, film, prose, movies and virtual experiences like video-games. Without making it a niche experience or laughing it off as an amateurish hobby. We can’t all experience archaeology through the 10-year excavation process, but we can make sure that experiences are accessible and inclusive. Why can’t video games, movies, TV shows provide a sense of interaction with the past that many kids might not otherwise have?

We can try to align these conscience efforts with meaningful actions that will fulfill our lives, but we can’t do it on an individual level it has to be done as a collective, together as archaeologists we can encompass all the properties of Ikigai to tell a story not fully told.